The Fruit Trees has been the recording project of LA-based artist Johnny Rafter for a few years now, just releasing We Could Lie Down in the Grass at the tail end of 2024, and a handful of one-off bandcamp-only recordings since. The most recent Fruit Trees album, titled An Opening, stands out in more ways than one. First and foremost, Johnny brought in friend and visual artist Hannah Ford-Monroe as lead vocalist and lyricist for the project. But An Opening finds its footing not solely within a new collaborative set up, but one that embraces the most instinctive feelings that came from the pair in a single sitting.

Described as “lightning in a bottle”, a night after the Dodgers opening night in LA, An Opening was written and recorded within a 3-hour sitting after a long day of work for both Johnny and Hannah. When no one else showed up for Fruit Trees practice, the pair set out to work on some harmony parts, as this was the first time Hannah had ever taken a stab at singing outside of the privacy of her car. Frustrated and tired, what came after was an unconscious flow of sweet, delicate melodies and open lyricism from Hannah, riffing on the warm, flourishing guitar voicings that Johnny plays with ease.

These songs flow out like an old fan; methodical, but slow in its rotation, bringing weight to the moments of pleasure and relief when that breeze finally hits your direction. Lines like, “I’ve got band-aids on my knees, I got them climbing trees, they have a face that looks up at me from a cartoon I haven’t seen”, are beautiful simply in their deliverance, especially considering being Hannah’s vocal debut. But beyond that, just the sheer coincidence that these images, these stories and these melodies managed to squeak out of her brain at that time, following Johnny’s worn-in directional paths, is worth a patch of momentary reflection at the very least. But rather than ask under what circumstances brought it out of them, circling the ever-shifting drain that is the subconscious, it’s easier to point at the amount of trust that blooms between both Johnny and Hannah, and the lengths at which their creativity will allow them to travel. These songs are rough, and rather imperfect (as the duo would say themselves), but that’s what makes An Opening such a beautiful anomaly. It’s an unintentional collection, placing Johnny and Hannah only with each other and what was around them, and deep down, trusting that that simple breeze will always turn back their way.

We recently got to talk to The Fruit Trees about trusting each other, leaning into imperfection and how An Opening came to be.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. We could have talked about baseball and sandwiches from Larchmont Wine and Cheese for hours.

SR: So really you two had no intention of making an album together?

Hannah Ford-Monroe: Absolutely not! [laughs]

SR: But here you are. I know this was all recorded one night after a shift at opening night at Dodger Stadium, but how did this idea come to be?

HFM: It was the opening day, so it was really busy, but you know, it’s the best job ever and I love it. But there was Fruit Trees practice that day, and I was getting off by 9ish, and Johnny lives right down the street from Dodger stadium.

Johnny Rafter: I had recently asked Hannah to sing harmonies in The Fruit Trees, so we were practicing older songs, working out the singing parts. That was really the only intention we had at the time.

HFM: Singing is still very new to me, so it’s not super natural for me to just sing a harmony part.

JR: We’re not trained musicians, so with harmonies, it either clicks or we could sit around forever trying to figure out.

HFM: I just wasn’t getting it right. I was just tired and it wasn’t hitting. And then Johnny was like, ‘do you want to just try writing a song?’

JR: Something like, ‘I’ll just make up guitar stuff, and you can freestyle over it for fun’. We had the mics set up because we had been singing through them, so I recorded it having no idea how it was gonna sound.

HFM: So Johnny would work out the guitar for like a minute or so, and noodle to find some chords or a riff, and I would listen as he was doing it, and then he would just hit record and start playing and I would just start singing. And that’s what you’re hearing on the album. Afterwards I had no recollection of what any of it sounded like.

SR: That’s insane! At any time during this session did you think to yourself that this may be something? Or did the realization come afterwards while listening back?

JR: At first I thought maybe we’ll come up with some ideas to revisit later and work into songs. But then midway through the initial recording session, I realized something special was happening— To me her voice is so beautiful and timeless and I’ve heard her sing in the car, and that’s why I asked her to join the band…

HFM: [laughs]

JR: And she’s my best friend, so it’s easier than finding some random person on Craigslist to sing with— but yeah halfway through, I realized what was happening was really beautiful.I was holding my breath for each song just thinking… ‘don’t mess up the chords’! [laughs]. Just keep going, let her do her thing. Then we’d get through the song and I would exhale. We wrapped it up at like one or two in the morning and I stayed up for three more hours listening through everything. I sent it to her that next morning like, ‘Hannah!!!’

HFM: It’s funny, because in my head I was like, ‘I don’t know’. You know? You know, I don’t know [laughs]. We were both so tired and worked all day, so it was this really special thoughtless, go-with-the-flow kinda state. And when you’re in a go-with-the-flow state it’s hard to gauge whether or not it’s actually good. When he first texted me the next day, I was afraid to listen to it. I haven’t really done music stuff. I don’t really know what my voice is yet. It’s kind of mysterious to me. But it really just simply appeared. One day we didn’t have an album, and then the next day we did.

SR: Johnny, when you were listening back, thinking of adding more parts to the recordings, how much did you try to honor what you recorded in that sitting?

JR: Luckily I had a few days off of work, so I spent them doing all the overdubs– mostly drums and harmony stuff. I tried to carry the same spirit– first idea, one or two takes. I tried to not overthink and trust that energy. I didn’t want to overdo the production because it felt like a special, small thing, like you’re there in the room with us as it was happening. It sounded sort of mysterious, and I didn’t want the production to take away from Hannah’s voice. I wanted that to be the focal point.

HFM: But with the whole timeline, we were both really exhausted after work, putting us into a state with my voice sounding like that after a day of talking and yelling, and then just the coincidence of our work schedules…

JR: If one little thing was different, like if one person showed up to practice, we probably wouldn’t have done this. It was so beyond our own intentions. I felt like we should just put it out in this form. It just feels special, even if there’s a lot of imperfection to it, maybe because of that.

SR: What’s your relationship with imperfection?

HFM: I like to draw, and taking it seriously is not the right approach for me. I feel like everything I’ve ever made that I’ve liked, for the most part, has been thoughtless, and just moving my hand without thinking about it. So for singing, I feel like doing it this way was the only way for me to start doing it. I’m not really the type of person who can sit down and really plan something out, and if I had tried to sit down and write a bunch of lyrics and melodies, it wouldn’t have turned out like this. I enjoy doing something just because, you know? Of course art’s not perfect. Nothing’s perfect. You can find an imperfection in everything. So why not just not care at all, and just be like, ‘yeah, that’s what I did. And?’ What does perfect even mean?

JR: Accepting the imperfection is the only way I can do it. I’ve always tried to embrace whatever happens, not trying to get a certain sound, and just sort of working with what is in front of me and what I can do with limited abilities versus trying to make something that’s technically perfect or something. A lot of the art and music I like looks and sounds kind of messed up. Homemade stuff especially, it feels so personal.

SR: Taking away from the noodling on guitar and riffing lyrically, what sort of things were you trusting in the moment? What was coming out that you wanted to follow?

JR: I think we both had a lot of pent up emotions, and it was just this emotional outpouring. It seems you weren’t like, ‘I want to write about this or that’. You were just kind of going wherever your intuition led. And for me, with the music in that moment, I tried to vary the structures and the tone of the songs. I feel like I would set the tone and then Hannah would build off of it.

HFM: Yeah, as Johnny was playing, I would be thinking about something, in general, to start off in a direction. And then it would just kind of… honestly, who knows where it came from? I was just kind of riffing off of Johnny. Maybe my brain would be like, ‘Okay, what rhymes with that?’ And then sometimes I was thinking about things that had happened recently or I would look at stuff that’s in Johnny’s practice space. I was thinking a lot about strings because there’s a lot of cables. As we kept recording, themes just naturally reoccurred. Like, now that word is in my brain, so when I can’t think of anything else, that’ll be the word that fills the space. It’s funny because when I was listening back, I talk about dreams a lot, but I don’t even really have very many dreams. I’m not a frequent dreamer.

JR: But life is a dream!

HFM: [Laughs] I don’t know, it’s like, how the heck did that all happen?

SR: As you’re parsing through these recordings, touching upon these feelings of silly or sad, were there thematic through lines that began to pop up?

JR: It’s almost in the exact order that we recorded it in. I think, kind of unconsciously, that I was trying to make an album. I was thinking, ‘well, if this was an album, what would be cool after that last song?’. That’s why it ended up flowing, I was trying to direct it in a certain way, and it all kind of fell into place. I can’t really speak for the lyrics.

HFM: I mean, I can’t either! [laughs].

JR: When I listened back, it felt cohesive. Like the songs sort of speak to each other in a way. There’s a lot of nice imagery and threads running through.

SR: The subconscious had a field day that night.

HFM: I think the last nine songs we recorded are all on the record. We just got into this flow state. And you really can’t think about it because you don’t want to lose it. It’s thinking about stuff that kind of gets in the way, you know? I can’t speak that much about music, besides this. What do I know?

JR: Instead of first thought, best thought, this felt like no thought, best thought.

HFM: Woah!

JR: The only thing in my life it reminded me of was last spring when I found a butterfly on the sidewalk on a super windy day. It was gonna get stepped on because it was hurt, and I picked it up and I walked like four blocks to my house, cradling it in my hands, trying to shelter it from the wind. That’s how it felt when we were playing. I was like, ‘Oh, my God! It’s such a delicate, beautiful thing. Don’t crush it!’

HFM: Dang!

JR: It was super emotional for me, listening to her sing and hear these melodies and words. It was just so moving. And then the whole weekend when I was recording, I would be alone recording the drums or something, and I would just start sobbing!

HFM: Johnny really hypes me up. I’ve always really liked to sing in the privacy of my car, but I’ve always wanted to write songs. I don’t play any instruments or anything and I don’t know how to make music at all. So Johnny inviting me into something that he does has meant a lot to me, because I couldn’t on my own. I needed someone else to invite me into their world. I’m grateful to Johnny for that. Honestly, I was really afraid when I went back to listen to some of the songs after. I didn’t want to listen to my voice, but I was surprised by how it came out. Even Alex [Favorite Haunts] asked me if Johnny pitched it up. I was like, I don’t think so [laughs]! I feel like I still don’t really know what my voice is, because I haven’t made anything before, so it’s been a fun surprise.

SR: How are you sitting with them now? Have you gotten over that fear of hearing your voice?

HFM: After listening to it a couple times, I feel more comfortable with it, for sure. I think it’s probably something that a lot of people feel when they first sing on something. I’d say there’s some nerves of like, ‘Oh, yeah, anyone could just listen to this’, but it’s fine. I feel more comfortable with it. I wouldn’t say I’m confident. But we made this album and we’re gonna put it out and just try not to think about it too much. Because, like I said before, that’s never really gotten me anywhere.

JR: I think sharing your voice is maybe one of the hardest things to do creatively, because it’s your physical body. There’s nothing you can do to change it, so it definitely takes some courage. I’ve felt similar things when sharing songs, but it goes back to the imperfection thing, it’s really just like, ‘this is what I can do’. I could either never share it with anyone or just put it out and move on with my life.

You can listen to An Opening out everywhere now!

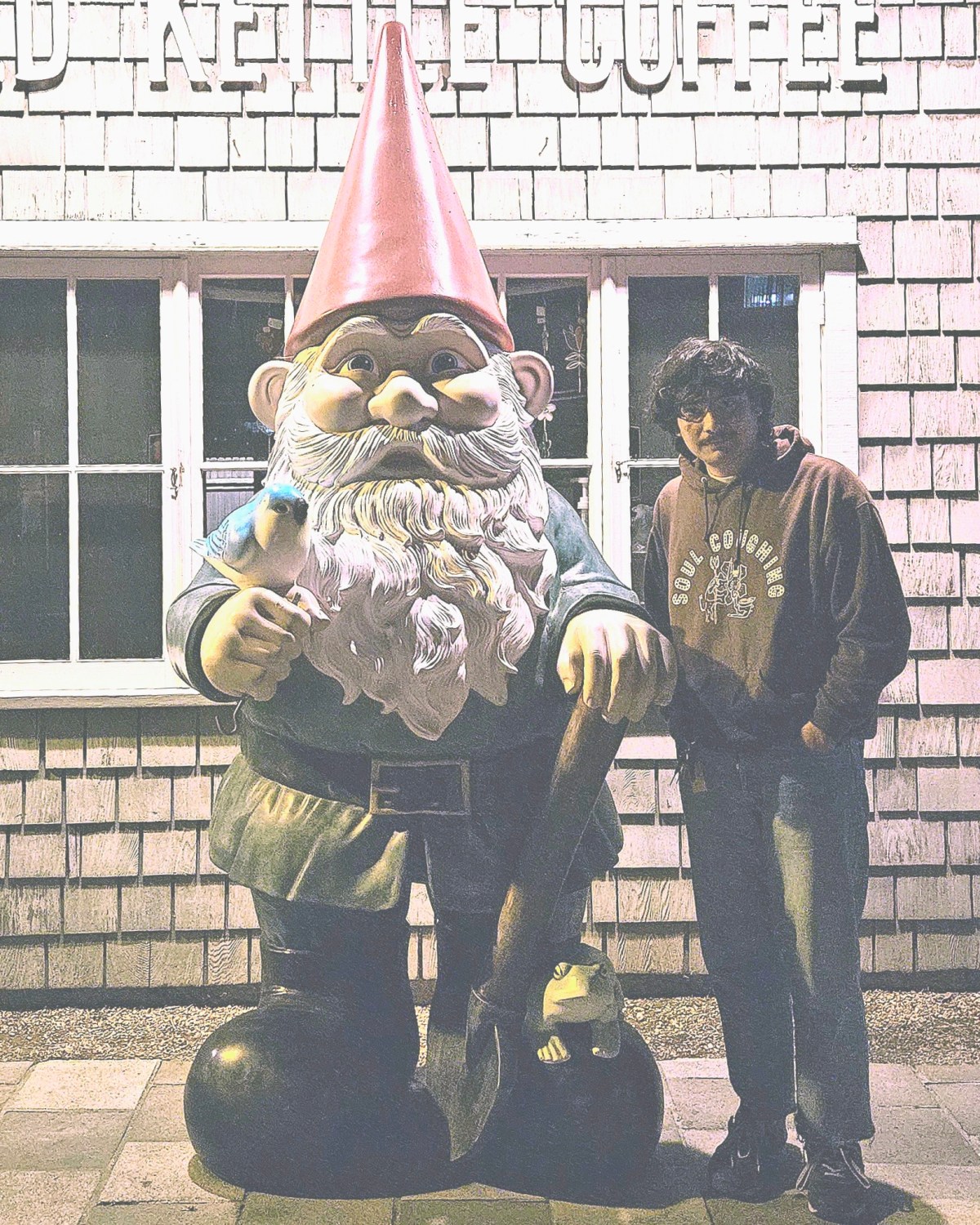

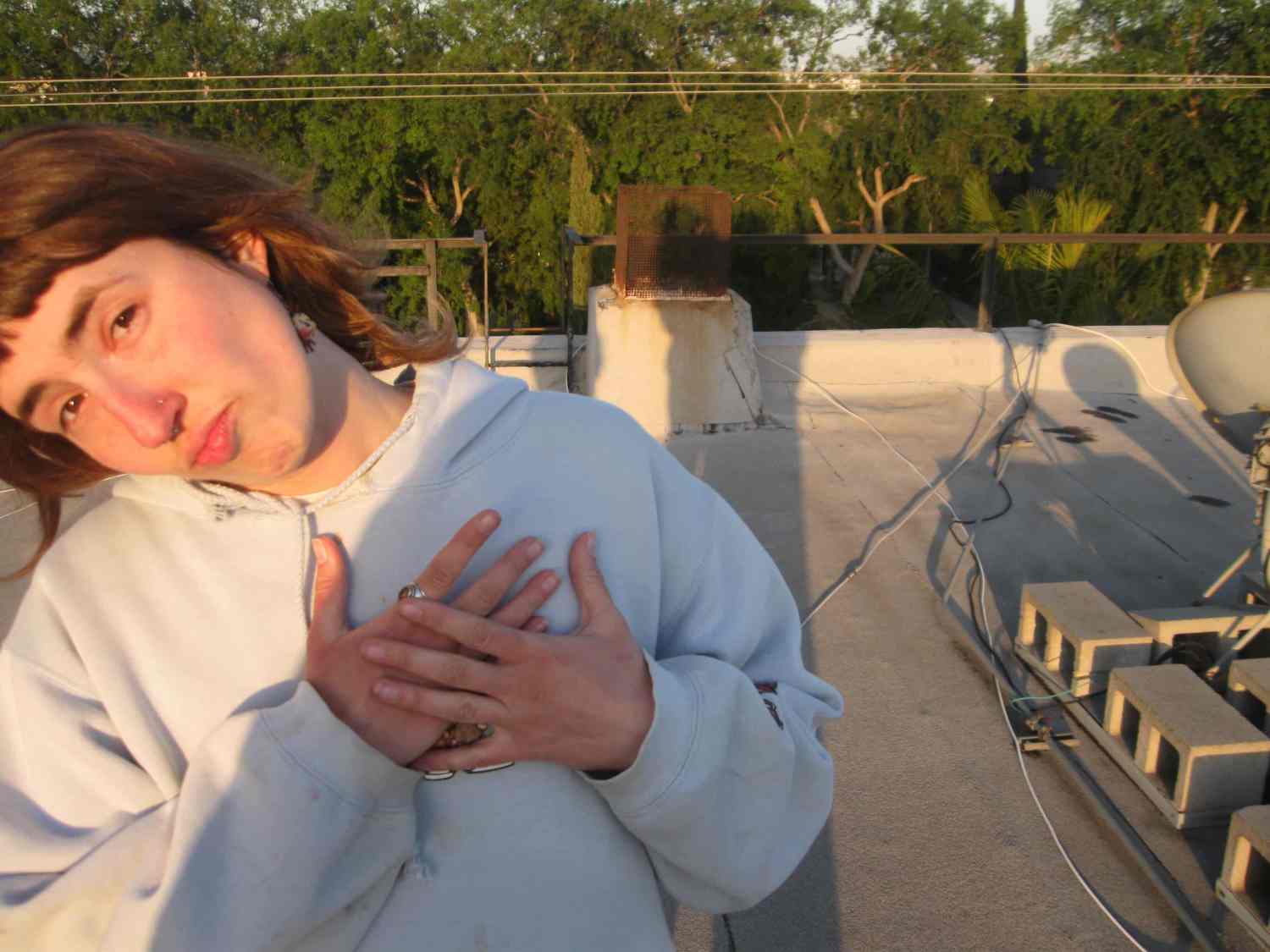

Written by Shea Roney | Featured Photos Courtesy of The Fruit Trees