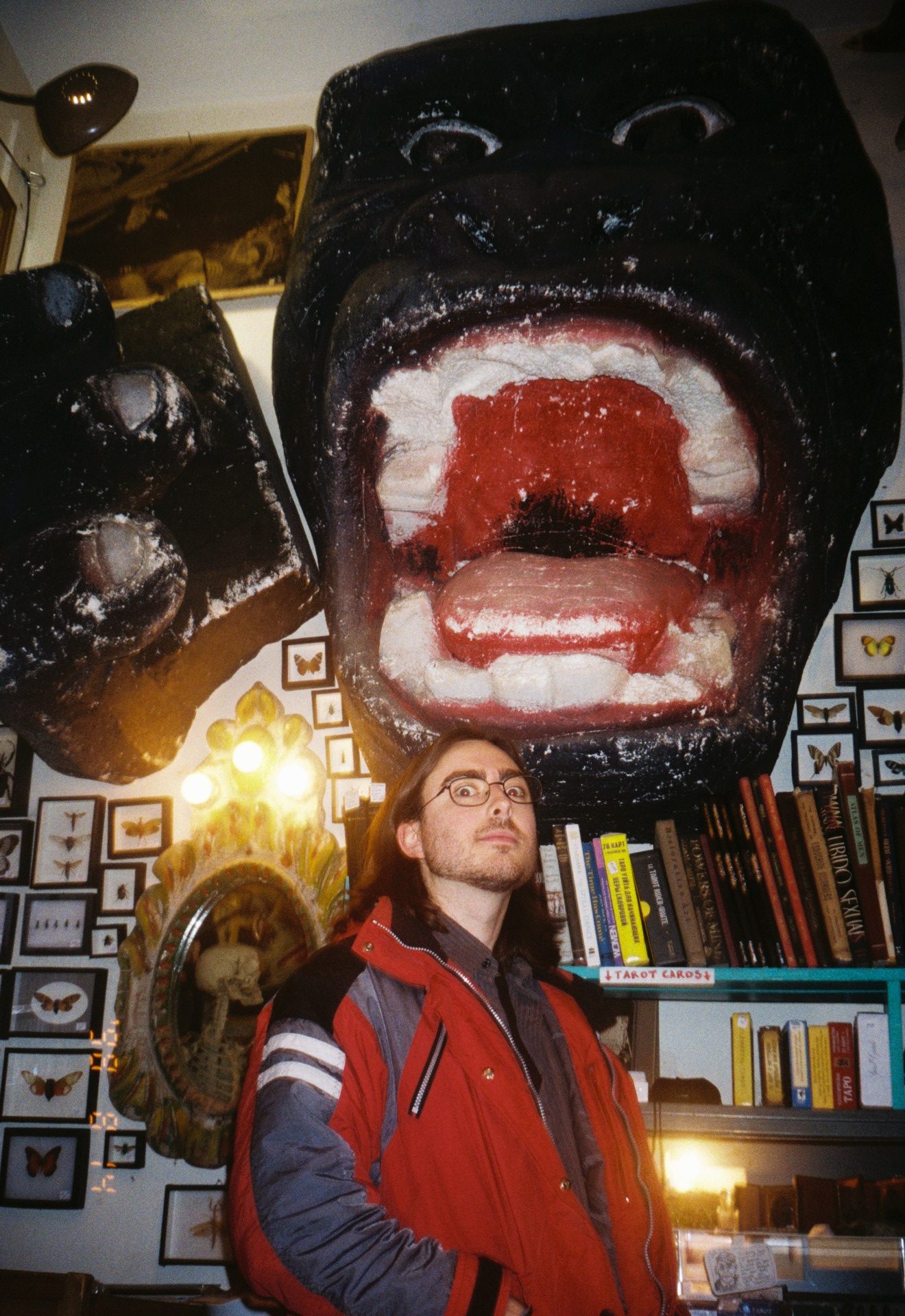

“Is there anything that came into this shop that you had to turn away because it was too fucked up?”, Chaepter asked the employee behind the desk of Chicago’s Woolly Mammoth Antiques and Oddities, the location we chose to photograph in – and one that left us grotesquely curious as to the collectables for sale. The taxidermied cow named “Meatball the Freak”, John Wayne Gacey original paintings, an old, preserved chicken nugget or a gun holster made from a squirrel, there was humor in both the disbelief and surrealism of it all that just barley cut the tension of how dark some of this stuff really was. “Hmmm,” she says, taking the time to give us an answer that would leave us satisfied in our inquiry. “I mean, people will bring in murder memorabilia all the time, stuff used in murders and crimes. But it feels weird putting monetary value to those kinds of things, so we often just trade for it.”

Chaepter Negro is a Chicago-based artist who performs under his first name, marking ground in his own unique and challenging ways with engaging and tactful sounds. Chaepter grew up in Central Illinois, rearing a large Irish-Catholic Midwest upbringing to show for it, where he was first exposed to music through classical training in cello and piano. But with the release of 2024’s Naked Era, a bold, brutalist post-punk album riddled with acute punctuation, searing guitar tones and strict melodic orders that carved out a new vision for the project and a trajectory that Chaepter and co. have fully launched into. Accompanying him are players John Golden on drums, Ayethaw Tun on bass, who have played with Chaepter for years, as well as the newest addition of Shane Morris on lead guitar.

Today, Chaepter shares a new EP called Empire Anthems, a brief and poignant collection of songs that are unwilling to mince words directed towards the fearful, and rather stupid, timeline that we are currently residing. Although gripping tightly to our being, blending punk antiquity and rage against the system with the absolute fear of what is unfolding in front of our own eyes, Empire Anthems plays out with urgency and condemnation, of course, but the purpose of its creation is a remnant of preservation. The kind of preservation you get from making art with the people you care about. The kind of preservation you get from engaging with and looking out for the community that you are a part of. The kind of self-preservation you get when you choose what has monetary value in your life, no matter how fucked up it is. Chaepter isn’t searching for fix-all answers here, but rather ways in which we can all push back when the things that matter the most are exploited.

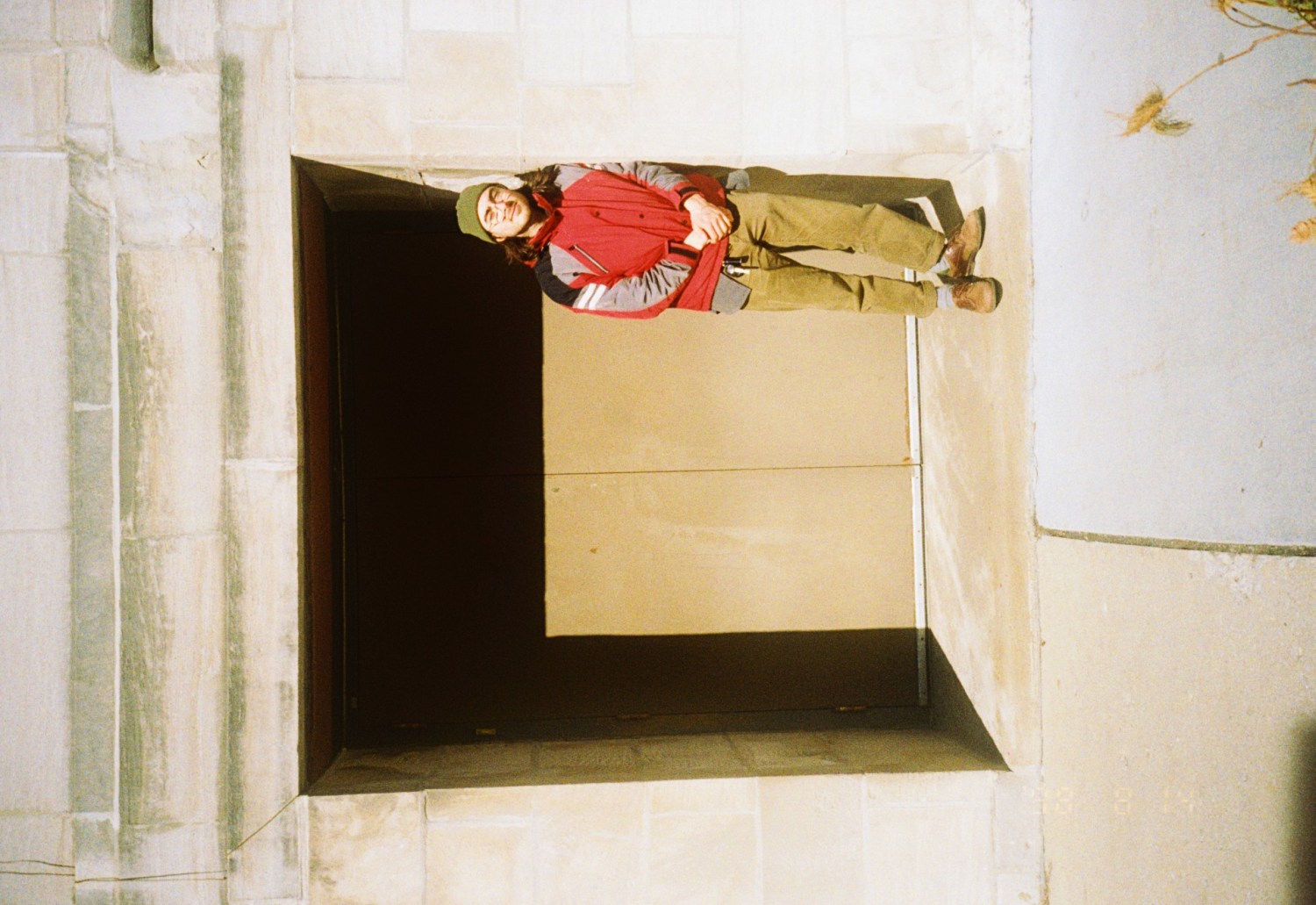

We recently spent the day with Chaepter, first taking photos in the Woolly Mammoth before we got to discuss Empire Anthems, having creative freedom in community and suffering from choice-poison.

This interview as been edited for length and clarity.

Shea Roney: So, you have an EP coming out soon called Empire Anthems.

Chaepter: Yes, we’re doing this EP with Pleasure Tapes. Honestly, it was kind of weird, the past year we’ve been touring the Naked Era record, and then I’ve been writing this other album and we just spent the last four months rehearsing and recording it – different from the EP. I just had a bunch of songs that didn’t really fit that, so we just spent a couple days in our practice space pushing through these songs. It’s like what would be the B-sides of an album or something, but we’re going to release it first while we search for a home for the bigger record.

SR: This EP is a continuation of that raw and bold sound that Naked Era fully embraced. As you venture more into this genre, exploring the techniques and sounds, what did you gravitate towards when fleshing out these songs?

C: I think for me it was just writing on guitar, and in this way, electric guitar. At the end of the day, I used to always write songs on piano, so I was always writing songs like that. It wasn’t until a couple years ago that I started structuring songs on guitar, and then also experimenting with pedals and stuff. I’ve always been doing quieter stuff, a lot of folk songs and stuff like that, but for whatever reason, it just kind of felt right to be part of a band. I’ve been in other bands, but I think what kind of led to that shift is I really like playing like this, where we can get loud and get aggressive, but also have those soft moments and have the dynamics, which we really try to do.

SR: Wanting to play louder, did you feel like you knew how to go into it, or was there trial and error?

C: Oh, definitely trial and error. I don’t actually even know guitar chords. I’ve just been doing my own tunings and my own chords, and just writing songs that way. I don’t know a C chord. I don’t know any of that shit. Everything’s been self-taught with guitar, and I think that’s been kind of nice because it’s forced me to do things a little differently. We were joking about that, because me and the band were at a show last night, and we were looking back at old videos of us playing and were like, ‘what the hell were we doing? What the fuck was that?’ [laughs] When I first started playing frontman and then playing guitar at the same time, I had just never done that, so it was a lot of trial and error, but we’re starting to kind of get to know each other a bit.

SR: When you bring a song to the group, how do you translate it to them? If you’re not referring to old music theory and stuff like that?

C: It really depends. We’re more collaborative now than when we first started. The Chaepter project was just kind of a solo project, and then I had friends that were playing with me, and we’ve gone through some iterations. But now we’re pretty much locked in as a band, and there’s a lot more collaboration. So I’ll bring in a song idea, and sometimes I’ll have a bass part written, sometimes not, sometimes I’ll have half of it. It’s just things like that. Oftentimes we’ll just do it as a three-piece. We’ll start fleshing it out, and my drummer, John, writes all his drum parts and helps with structuring. Unless we’re collaborating with someone who’s doing lead, we keep it pretty open. Sometimes I’ll come in with a song and it’s pretty much all done. Sometimes I’ll just have a riff, and we’ll see where that goes. It’s just been really good for my brain, and just us as a unit to push and pull.

SR: Do you feel like this freedom in your abilities, and lack of quote-unquote musical structure, has helped you explore and start writing in different ways?

C: Yeah, for guitar music at least. I was raised playing classically on cello and piano since I was six. I have that experience in theory and stuff, but in terms of guitar, just not knowing what I’m doing has been honestly really cool. Anytime I kind of figure something out, it feels very fresh to me, or naive in a way that I feel comfortable in. I would naturally play this way for whatever reason as opposed to feeling like I have to do something because someone taught me since I was a little kid to do it like that.

SR: So now as you gear up to release Empire Anthems, referring to these songs as almost B-sides to an album, was there a connective tissue or theme that runs throughout them all?

C: They were kind of just existing in their own kind of space. I’m also working on another record, too, so I’ve kind of had three or four records, or at least collections of songs, working off in different places. These songs were just in their own sort of world – its own darker kind of space. I was in a weird spot post-album. Whenever I’m done making a record, I get a little depressed, so I was just kind of thinking a lot about the relevance and utility of making art in a fading empire that we are currently residing in, and how that intersects with our cultural identity, and this idea of ‘Empire Anthems’ being these cultural signifiers that kind of lulls us into complacency and reaffirms the dominant American culture and rationalizes irrational American terror. You know, you turn on the radio and some pop song that’s making you not really think about something, but allowing you to continue to sleepwalk through life. How does art exist in that kind of way? These anthems just keep pulling you back into the Matrix or wherever the fuck we’re in [laughs].

SR: Yeah, I was very intrigued by the word ‘anthem’ in the title, because there is such a notable heaviness to the word. But also repeating the word ‘signifier’, can you talk about these songs as signifiers and this plane that you created?

C: The idea of art as a cultural signifier in general, being something that in music’s case, if you’re living in a certain culture, you’re going to produce certain cultural products that reaffirm what it means to live in American culture, which is this blood-sucking empire that’s on its last legs. How dominant art might be shifting, just to keep the dream alive even though it’s not there anymore, that’s just what I was thinking about. Art is obviously what I’m doing, it’s my life, and sometimes it’s the most important thing in the world to me. And other times, I gotta focus on my family. It’s this sort of oscillation back and forth of being a ‘god-like’ thing in my life pulling me towards something, but also something I’m just doing. It can feel kind of silly just writing songs in the state it is right now, but it is deeply important at the same time. I guess that’s all things.

SR: I would argue it’s always important, especially with all that comes with it, especially community, which is something that you are very vocal on. This was huge for you with Naked Era and that press, you’re very keen on giving your surroundings voice and appreciation. Thank you. What bits of this relation and respect for your surroundings sticks with you when making art?

C: I feel like in my brain, what comes out is pretty much a debris, just kind of an after. So if making art is a fabric, it’s that community that comes with it that I think matters the most. It’s kind of reflexive – it’s a mirror. So if you’re involved in a really active art scene, you’re inherently going to be injecting that into what you’re making. Whether you’re doing it explicitly or tacitly, it’s always going to be part of it. That’s something my band and I try to focus on, that process and journey mattering more than the song that comes out of it. Because at the end of the day, as artists and creatives, that’s what you have. Once you let that song go, it’s out there, but you have that journey with you forever. So inserting yourself in something and allowing yourself to be part of a scene or some sort of artistic collective fabric is the best part of doing all this shit. I spent so many years of my life making songs alone in a bedroom. It was fine, but you get out what you put in. There’s nothing wrong with writing in an isolated manner at all, but nowadays, I’ve been feeling so good about being around other people that are making stuff, and part of this greater thing.

SR: Even to the stories you tell in your songs, there is this level of presence and characterization regardless of if it’s told from your eyes or not. There is always this presence. So when it comes to dealing with conflicting imagery, you know, with this failing empire, what kind of emotions went in and came out of these songs in the process?

C: Yeah, I mean, post-album with these songs, I felt like I was just steering a ship in the dark, into the fog. It’s getting foggier and it’s very confusing – I get overstimulated. I was kind of in that space where I was just like, ‘what the fuck am I doing?’ Not in any way that’s rooted in that much reality, but I was getting very existential. I think that’s where these leftover songs and how they kind of form into this EP. It’s a weird thing, once you’ve given life to a new project. For me, it’s kind of an obsession. I’m obsessed with something for a long time, and then you finally put it to tape, and then, ‘dang, here it is’. That’s kind of the headspace I was in putting this record together. And then, you know, watching all the systems around us degrade at an even more accelerated rate than they have been doing so previously – there’s a lot going on to say the least. And again, it can seem so silly to be writing a little song, but it’s serious. And I think being able to balance both is important.

SR: Sorry, are you blinded? This window is brutal.

C: I am cooking. Part 2 on the bench out there?

*change of scenery

SR: I can’t remember what we were talking about

C: I was saying anything I needed to. I was in survival mode [laughs].

SR: [laughs] How long have you lived in the city for?

C: Since October of 2019. I moved here after I was in Madison for a little bit after college working and then moved here. Then COVID happened.

SR: Hell yeah. You have described your project in the terms of Midwest Gothic, which I really appreciate having lived here all my life. I feel like in a way that really helps make this Empire Anthems a little bit more credible, growing up in the heart of America with a big classic big family. Looking at the world you grew up in and then the world you are in now, does that live in these songs at all?

C: I feel like everyone who grows up in the Midwest has this sense of space because we are just in this plane. When I’m writing songs, I do try to channel that a lot. I grew up in Central Illinois in the country. It was really lovely being able to grow up around nature and be exposed to animals and having that big family, but there is sort of a Midwest existentialism, I guess I will call it, that feeling of living sort of nowhere all the time. Illinois in particular, and what happened to this state and what it looks like now with industrial agriculture and losing the prairie, is something I’m always thinking about and trying to channel into the music. There’s a big history of lost connection to our land here in Illinois and the Midwest in general because of industrial agriculture and what that’s done to farming communities. There’s a lot of ruins around here. You can go over to Michigan, or go to Gary, Indiana you know, an hour from here, and see with your own eyes what that looks like when people just get left behind. I was thinking about that a lot with these songs, just that expansiveness that we’re looking across. We can see everything in front of us in the Midwest.

SR: Did you find any hope buried within these songs? Or are we.. are we pre-hope?

C: [laughs] I feel like these were probably my least hopeful in a minute. These songs were kind of like a shot, you know, these five songs, just like an injection. I don’t know what’s going to happen after the injection. Whereas with a full record, I feel like I tend to be able to have emotional arcs with them and I’ve never been a huge fan of writing EPs. I’ve always felt I’ve struggled with encapsulating a full concept in them that I can do in a record. But that’s why I kind of view it as a shot, it’s just one big injection. There’s maybe not the catharsis that a full record has.

SR: I mean, to call back to before we were recording, we were talking about exposure therapy, and it’s kind of ripping off the bandaid in all aspects. Do you find yourself taking too much on at times?

C: These songs, and just a lot of the music I have been kind of consuming as of late, fall into that sort of ‘rattle ya a little bit’ category. Not in one particular sort of ideology, but just like this idea of like, things are not right per se, and if you’re feeling like something’s off, that’s not probably innate to just you, you know, it’s a fully human thing. It’s like, if you’re ill, you’re mentally ill because of this or, you know, the sort of individualized blame that it’s really easy for us to go into and to sink into that shame, you’ve got to give yourself a little bit of grace, you know? Recognize that to some degree we’re doing what we can, don’t be so hard on yourself. Maybe it’s growing up with Catholic guilt, I find myself doing so much, and I’m trying to be better about it. I don’t think we should have to be able to keep up with everything that’s going on, especially, in terms of new technology and productivism and feeling like we have to be this well-oiled, perfect little production machine as a human. It’s like, ‘nah, man, this shit is so confusing’. It’s hard to keep up and it’s not normal for the human brain to have all this fucking stupidness all the time

SR: What constitutes a break for you?

C: Oh, I’m so bad at trying to just chill out. I have a lot of family stuff that’s always going on. Eight siblings, very dysfunctional, and trying to balance that with making money and doing music, booking tours and doing this music thing, it’s just so much work. I love it, it’s an obsession, but it’s a lot of unpaid work, so it’s hard to do and balance a job. I’m reading more, which has been good. I deleted Instagram from my phone last week, I was like, ‘this shouldn’t be that big of a deal’, but it was. It’s really difficult because I use it to book tours, so I’ll message a band, and then like an hour later, I’m like watching fucking videos of AI squids being cleaned off. That’s why I deleted my Instagram. I saw this AI video of someone washing off a giant squid in a boat and I couldn’t tell if it was real or not. I was like, ‘this is fucked up. I got to get rid of this’. I was sleeping better and when I wake up, I felt just a little bit better about how much time I’m spending consuming things that don’t affect me. Obviously, we’re veering towards absurdism, but at some point, I just need to disconnect and be like, ‘okay, I’ve got friends in front of me, family, people I love that I talk to and talk back to me’. I also got rid of streaming, which has been fine, but I don’t have a lot of money to buy records so I’ve been doing YouTube and bandcamp and buying friends stuff that I really, really love.

SR: How has that been? Did it bring out anything with your relationship to listening or something?

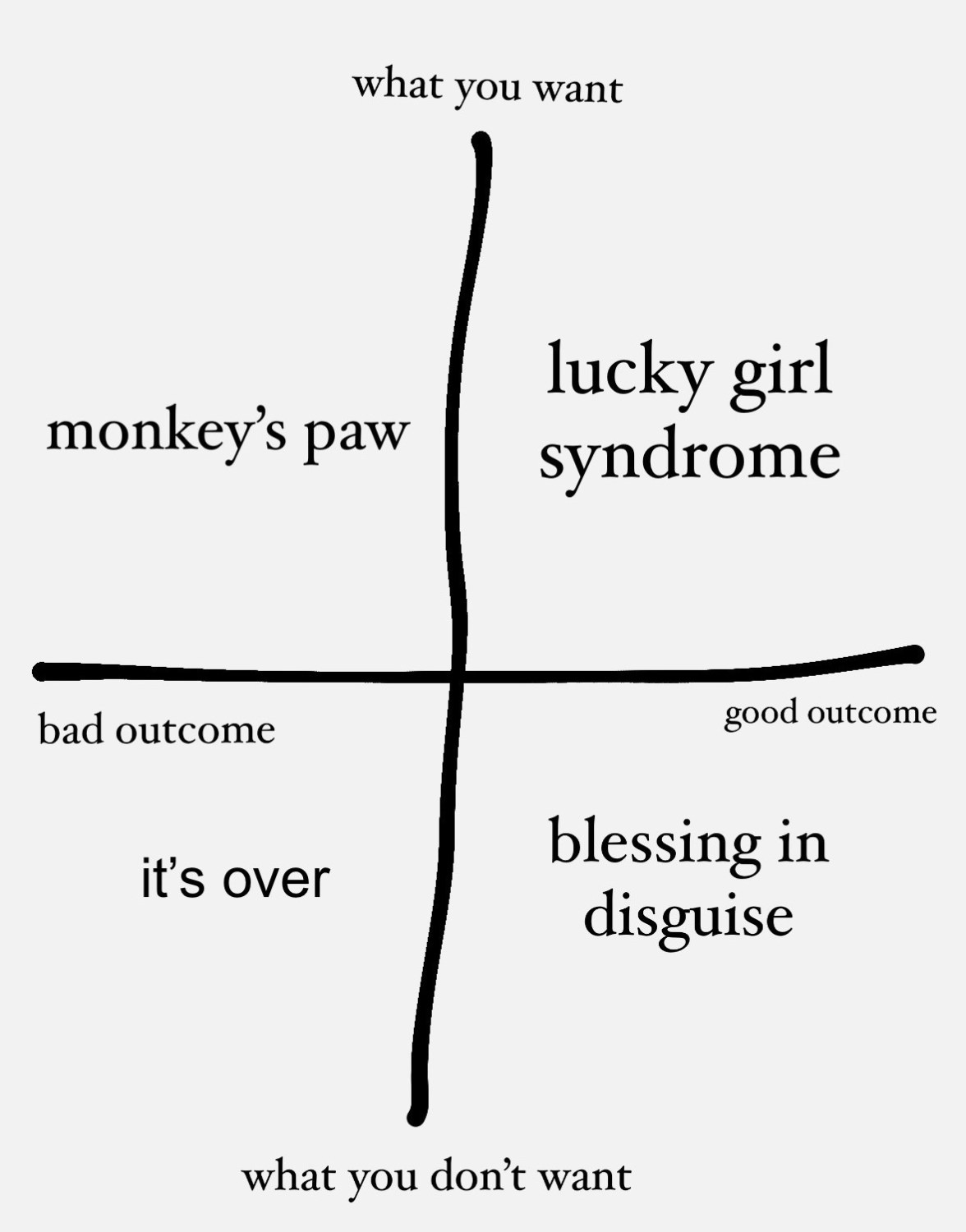

C: I’m trying to find a balance with music because we’ve kind of been conditioned to view it all as free. Even as someone who makes stuff, I grew up with CDs – I first fell in love with music with CDs; buying CDs, getting CDs from the library, burning them, getting them from friends – it was a little more precious back then at least. I got streaming in 2018, and whether you think about it explicitly or not, it does reshape how we interact with and appreciate art, you know? I’ve just been trying to make some small changes where it’ll force me to go a little slower with stuff. Because otherwise I can be kind of overstimulating myself. Something I always think about is choice. I think historically, humans aren’t actually that good with choice, which is why I think the capitalist idea of choice in terms of products and things you consume is like a mirage. We’re good at looking back and rationalizing stuff, but when I have all these choices in front of me, I just get choice-poison – I just don’t know what to do. So I feel like limiting myself a little bit and being like, ‘okay, I can listen to this today’. I remember one summer driving my mom’s car, she had a Feist CD, and you know, I was like, ‘I don’t know what this is’, but I fell in love with it. For that whole summer, that’s the only CD I had in the car, and every song I got to love.

Scroll for more photos with Chaepter

You can listen to Empire Anthems out everywhere now via Pleasure Tapes. Chaepter will be playing an EP release show this Thursday 3/20 at Empty Bliss in Chicago and then will embark on a short tour working their way out east. Look for dates and cities here.

Interview and Photos by Shea Roney